Thank you to everyone who tuned in last week to watch The Remember Balloons on PBS.

We had 89,000 viewers! Your messages, your reposts, your love — I felt it all.

And an extra shoutout to the 11 of you from The Block. who’ve already given to our Hold the Story: 1,000 Gifts for a National Moment campaign — I’m humbled and grateful.

We’re trying to get 1,000 people to give $100 so if last week’s viewing meant ANYTHING to you please consider helping us build something bigger for national broadcasting! If you haven’t yet, you can join in at the link below.

JOIN THE MOMENT HERE

Reminder: The closer we get to 100 of you on our side before we go public with our campaign the better chance we have to get people excited!

With Great Power Comes… a Great Substack Intro

I want to take a moment to acknowledge the wave of new folks who joined The Block. last week in order to see The Remember Balloons.

You haven’t just subscribed to a newsletter — you’re entering a community. One that takes pride in reflecting, asking questions, telling stories, and wrestling with the beautiful, complicated intersections of life. I just want to say: Welcome.

Okay, everybody. When I started this Substack, I told you this space would be different. More investigating. More intersecting with society — from arts to sports, politics to race, faith, movies, TV, and everything in between. I write where the spirit leads me.

With that in mind, let me set the table for today’s topic.

Hello. I’m your friendly neighborhood race man!

This essay is an exploration of a real-life event that touches on race.

Now, if that’s not what you came here for… well, you might wanna hop off the boat now. But if you’ve been rolling with me for a while, then you know: I don’t shy away from difficult topics.

So stick around.

Because you know what they say:

With great power comes... a Substack essay about a burning plantation on a Wednesday!

Let’s swing in.

I didn’t always see it.

Not because I couldn’t, but because I didn’t want to see it.

For a long time, I didn’t care much for Black history. I thought my community spent too much time stuck in the past. Little did I know I was part of the history I was avoiding, both as a descendant of enslaved people and as a beneficiary of land taken through colonialism.

I believed our history was an anchor, dragging us back when we should be pushing forward. Every time someone brought up slavery, Jim Crow or the Middle Passage, I rolled my eyes and thought, “Here we go again.”

So if you had taken me to a place like Nottoway Plantation back then, I wouldn’t have felt anything. To me, it would’ve just been a big beautiful house. And if someone told me they were having a wedding or a dinner there to try to “reclaim” the space, flip its history, make it a place of joy and healing—I would’ve nodded along with that hippie shit.

Like, sure, that’s radical. That’s poetic. Why not?

But it changed in 2016. I was working on my show The Black Card Project and for the first time I had to really dig deep into my people’s history.

I learned what the phrase “Strange Fruit” really meant. I learned about the darkness that is the history of the American “picnic”. And for the first time, history started to become alive.

I did a section in the show called “Are You Woke?”—this was before “woke” became some political code for “liberal”. Back then it was a warning Black folks gave to each other.

“Stay woke.” Keep your eyes open. Don’t get too comfortable. There are systems and people out there working to erase you if you’re not paying attention.

And that’s when I really started to see it.

Heritage is Complicated

Now, I know I’m moving into the complicated topic of Heritage.

Everyone deserves to be proud of their heritage.

It’s your identity.

It’s where you come from.

And all of us, no matter who we are, have pieces of our ancestry that are shameful right next to the parts that are proud.

Two things can be true at once.

But we can’t talk have a honest conversation about heritage if we aren’t willing to hold both truths. If we cover pain with celebration, or rebrand symbols of oppression into party venues, we’re not reclaiming, we’re rewriting.

So I’ll go first:

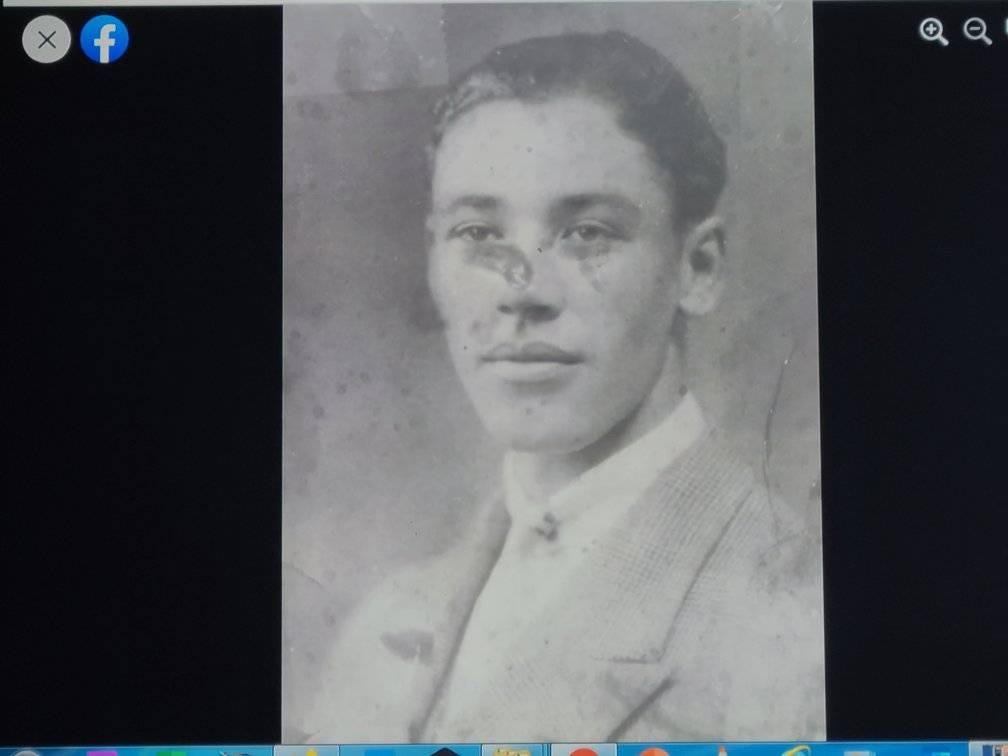

His name William Moore.

My great-grandfather.

Born in Macon, Mississippi.

Post-Reconstruction, but not post-oppression.

He had 7 kids including my Grandma.

William came up to Ohio as a part of the Great Migration. Escaping the brutality of the Jim Crow south.

Legend has it. William’s last name used to be Younger but he killed a white man in the South, fled North, and changed his last name to “Moore”.

In line with that myth, William had an unfortunate infinity for harming people.

There’s the story of my Grandma’s oldest brother, Sunny Boy, being hog-tied to a basement pole buck-naked while William beat him. That’s until Sunny Boy escaped, and ran away from home for some time. As my Grandma tells it, she & her sibling eventually found him working in a manufacturing yard.

My heritage is coming from a man, who was a survivor of one of the darkest times in American history, and was the creator of what may have been the darkest times in the lives of his children.

That’s part of my heritage. It’s a part of what I carry.

So when I heard about a large fire at a Southern Plantation last week, the word “reckoning” started whispering in my mind.

Let the White Castles… Burn?

It was once known as The White Castle. Built in the 1800s by a sugar baron from the Randolph family, it stood as a monument to wealth, status, and Southern grandeur. Majestic white columns, wide porches, and pristine symmetry, this was a house designed to inspire awe.

Art as a symbol of power.

But all symbols carry intention, and intention carries weight.

Like all art, these places are imbued with meaning. Not just by their creators, but by the way we interact with them.

SobBefore we go any further let’s name a meaningful truth here:

The Nottoway’s existence is inseparable from slavery. It’s not speculation. It’s a documented fact.

The beauty of the mansion came from forced labor. From the sweat and suffering of enslaved people who built the foundation, harvested the sugar, cooked the meals, nursed the children, and maintained the grounds every day, without pay, under the constant threat of violence.

We know the Randolph name. Thomas Jefferson’s daughter Martha married Thomas Mann Randolph Jr. while John Randolph of Roanoke freed hundreds of enslaved people in his will. Richard Randolph of Ohio gave his entire estate to former Randolph family slaves—money that eventually helped found Wilberforce University, a historically Black college.

These stories complicate the legacy. But they do not cleanse it.

Because we also know what happened in these homes during the height of the antebellum South:

People were enslaved.

They were bought. Sold. Worked to the bone. And through it all, they endured.

(If you feel like eye-rolling…just stay with me)

So yes, maybe the house was beautiful. But it was not innocent. That beauty came at a cost.

And last week, The Nottoway Mansion…I mean Plantation burned. And when I saw it, I felt electric. Like my southern ancestors inside me playing a joyful jubilee of the blues on a Friday night.

And the first thing I told my wife Ashley when I heard the news?

“I’d take a picnic, sit out there, and watch it burn forever.”

I meant it. And I know how that sounds.

Because picnics have a twisted history. White people used to throw literal parties at lynchings of Black people. Phillip Dray, a writer and historian of political history, stated:

“Lynching was an undeniable part of daily life, as distinctly American as baseball games and church suppers. Men brought their wives and children to the events, posed for commemorative photographs, and purchased souvenirs of the occasion as if they had been at a company picnic."

-Phillip Dray

So yeah, when I saw that mansion burning, my first reaction felt like justice. A reckoning. A kind of ancestral exhale.

But the longer I sat with it, the more complicated it became.

All while I’m going off—here I am, a Black man now owning property…land that was taken from another people group through violence and pillage. And I’m benefiting from it.

So even in my pride of reclaiming space as a Black homeowner, I’m tangled in the same colonial roots that shaped this country.

Reckoning with Memory, Heritage, and Justice

(A Ghost Tour?!? I hope my ancestors Casper the Ghosted one of these dummies!)

So yeah, it’s complicated. I mean…it’s heritage.

And I’m trying to figure out how to acknowledge and sit with the erasure of indigenous people while still feeling proud of black ownership in a city where redlining was used during the failed Urban Revitalization policies of the 1960s to rid of an entire black neighborhood (for my Akron folks, I’m talking about the Innerbelt). And I don’t have an answer but I’m reckoning with it.

But there’s also got to be some base line discussions here about the use of structures like the Nottoway right?

When I see Nottoway described as “restored to her days of glory,” I have to ask:

Would you like to explain those *checks notes* “days of glory”?

What we choose to remember, and how we choose to remember it, shapes us.

We don't host parties or weddings on the grave of American Revolution sites.

There is a respect — a reverence — for what happened there, especially when death was involved. And yes, with troops, we see them as heroes. That’s “how” we choose to remember.

So should we not also see those enslaved people as heroes?

Folks who endured so much — culture taken from them, families separated, bodies used for someone else’s gain — and still continued to live.

Isn't that heroic? Aren’t heroes those who put their lives on the line for the betterment of future generations?

So, a place like Nottoway Plantation… should it not be treated more like a sacred site then?

A respected burial ground for those who fell fighting just to stay alive?

Heritage is complicated, but not every part is gray. There has to be a foundation we agree on.

Enslaving people is bad.

Killing people for their land is bad.

We all benefit, in one way or another, from those acts happening.

So when we stand before structures that symbolize those histories, like a mansion built by enslaved people , shouldn’t we treat them as sites of reckoning?

Not to erase them. But to remember. So it never happens again and so we can look honestly at the policies and practices that exist now.

So, a place like Nottoway?

Yeah, I cheered when it burned. And part of me still does. But I also know fire doesn’t solve anything.

Fire might clear the ground but it doesn’t rebuild what was lost.

And if I’m being honest, this story isn’t really about that place.

It’s about what that place exposed in me.

Because I’m still unlearning.

I’m still noticing how quickly I tune out when history feels too heavy, or too slow, or too… repetitive. Especially if my identity doesn’t put me on the right side of that history.

And I’m still working to remind myself: repetition is how we remember.

I used to believe that forgetting helped us move on. Now I see that forgetting is what got us here.

I’m not above the problem. I’m inside it.

So when I ask these questions—about memory, about heritage, or about how we treat sites of suffering, I’m not pointing fingers. I’m holding up a mirror.

For me.

For us.

Because if the people who endured those plantations were heroes…Then what kind of descendants are we becoming, if we let their battleground be marketed and sold for someone’s Instagram feed?

I don’t want to be another person who looks away. I want to be someone who remembers on purpose.

So here I stand, between the ashes of the past and the uncertain ground beneath my feet, trying to figure out how to be both heir and witness, without forgetting either.

But also…

stop with all the hippie shit.

(NOOWWW, you may eye-roll..😉)